Substack Library

GlossaryThe Post-Covid Financial Hangover

July 10, 2025“Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

-Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises, 1926

THIS IS NOT INVESTMENT ADVICE. INVESTING IS RISKY AND OFTEN PAINFUL. DO YOUR OWN RESEARCH.

Present circumstances echo past events. Today’s political and economic landscape echo the policy responses to the 15–20 million deaths from COVID. Early in the pandemic, the efficacy of mRNA vaccines was unknown, leading governments to borrow in what now appears to be an excessive amount to fund emergency measures. Covid is gone and the debt remains. The legacy of this response includes: a) large budget deficits and b) leaders’ refusal to acknowledge a simple truth—reducing deficits requires raising taxes and cutting spending. This challenge transcends countries and ideologies.

Post-COVID Economics

To simplify, consider three major economies: the United States, Germany, and Japan. To be sure, significant differences exist. Japan is experiencing a profound demographic shift via immigration, Germany is contending with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and reduced U.S. defense support in Europe, and the U.S. is experiencing an abrupt shift toward populist politics. Yet, all three grappled with COVID and inflation.

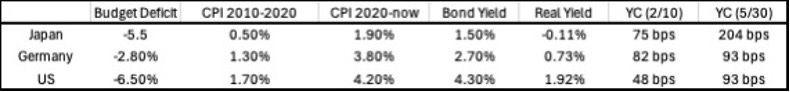

The table below summarizes their budget and inflation conditions and different measures of bond yields (nominal yield, real yield, and the relative yields across different bond maturities).

The “hangover” is the challenge of managing inflation and deficits, compounded in Germany’s case by an increasingly aggressive neighbor. It takes a long time to recover.

Several key trends stand out:

a) the U.S. and Japan face large budget deficits, while Germany’s deficit is poised to increase;

b) inflation was low for the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, but since 2020, the average has been significantly higher, in part because wage settlements can take years to come back to earth. Now tariffs are once again disrupting the equilibrium;

c) bond markets are beginning to demand a premium for governments borrowing heavily, as reflected in the steepening yield curve, which then exacerbates the debt sustainability issues.

These issues feed on one another in a self reinforcing and negative way. Below, I show the U.S. yield curve. Note the recent spike in relative yields, with 10-year yields rising compared to short-term yields.

While the moves have been big, they can be much bigger. Over the past two decades, 10-year Japanese government bonds have yielded approximately 50 basis points (bps) above 2-year yields. Currently, that spread is 75 bps. In the U.S., the historical average spread is about 83 bps, so the current spread is below average. In Germany, the average spread aligns with current levels, but, as in the U.S., this spread has risen significantly. The bond market is signaling to politicians, particularly in the U.S. and Japan, “get your act together.” However, politicians are doing the opposite because…incentives matter. Their incentive is to be popular and the things required to change this dynamic are not popular and never will be.

Post-COVID Politics

This week, Japanese bonds sold off after a poll suggested that the opposition Democratic Party for the People (DPP) might perform better than in elections later this month. To address post-COVID inflation, Japan’s recent inflation prints are above 3%, the DPP proposed tax cuts despite a 5% budget deficit, a terrible policy that risks exacerbating fiscal imbalances. In the U.S., Congress passed legislation that will widen an already large budget deficit. Germany is also heading toward larger deficits, though extenuating circumstances justify this. While I don’t include a chart for the UK, a similar dynamic occurred there last week, where a modest attempt to cut spending triggered political backlash.

What stands out is that the policies of the DPP in Japan, Republicans in the U.S., and Labour in the UK are disconnected from economic reality but tightly tied to political expediency. Any politician who campaigns on raising taxes (which no one likes) and cutting benefits (which no one likes) risks alienating everyone. Consequently, no one pursues such a platform, regardless of political ideology.

This suggests that excessive government spending will persist until markets force a correction. Will that happen? Like Hemingway said, probably slowly and then quickly. Several factors could drive bond yields higher: too easy Fed policy would be a rapid trigger; prolonged deficits would increase government interest payments, deepening the fiscal hole; or investors, wary of these risks, might simply refuse to buy long-term government debt. While I generally like investing in bonds, at present I am picky about which ones I will own and in some cases am outright short.

Now out in Korean, Italian, Estonian, Chinese and many other languages:

The Uncomfortable Truth About Money